As I celebrated my 65th birthday and over 40 years working in the sport and leisure sector one fundamental failure overshadows my career. Why have we failed to address the equality gap in participation levels?

When I joined the profession in the late 1970s it was at the time of the Sports Council’s first campaign "Sport for All" and the birth of sports development, both designed to address equality in participation. Despite huge public investment in sport and leisure, it was clear that the opportunities mainly belonged to sporty, white, male, middle-class users. Women, black and ethnic minorities, disabled people and poor people were all under-represented compared to the population at large.

Forty years on and, although overall participation rates continue to marginally improve, inequality in participation has remained stubbornly static despite all our efforts and all the funding given to sport and leisure by successive governments and councils. Over my career I have been part of numerous different campaigns and attempts to measure and improve participation rates but when I look at the latest This Girl Can campaign and review the data now presented in the form of Active Lives what I see is just how little has really changed in all that time. I cannot help but ask myself: why?

Over recent months sport has been under increased scrutiny for both its perceived behaviour at the elite level and its performance at the community level.

At the elite level claims of sexism, racism, homophobia, cheating, bullying and lack of athlete care have become more common. The fact that these behaviours have not been dealt with is due to both poor management and failures in governance. But are these behaviours simply the unacceptable side effects of the absolute focus on winning or are they indicative of a more serious systemic failure in values and empathy in this part of the sport system? And does the obsessive focus on winning at any cost undermine those of us trying to encourage the uncommitted to participate?

Meanwhile, the government has challenged community sport through Sport England to increase the opportunities for those currently under-represented particularly those in greatest need to improve their health and wellbeing. The clear implications of the new Sport England strategy and funding decisions now emerging are that some of the traditional providers of sport and activity, such as the national governing bodies of sport (NGB), their associated local clubs, councils and their local facility operators, are seen as not being able to address equality in participation and are being replaced by new relationships with organisations seen to be more in tune with the under-represented audiences that can benefit most from greater activity. Not fair, say those losing funding but I'm not so sure.

When I was at secondary school I was very overweight and was regularly excluded and almost abused by the sport teacher. I was given no encouragement to participate whatsoever. All the positive support went to those that could make the school teams and win for the school. Yet at night I spent hours playing football and cricket on the local park. Only in the sixth form, when I discovered I was good enough at badminton to represent the school, did I receive any positive recognition and encouragement. This experience greatly influenced the rest of my career.

When some years later I worked in the inner city of Coventry I found similar feelings of exclusion among local people who felt that the local Foleshill Baths and the big city-centre Pool Meadow swimming pool and sports centre were not for them. The creation of Action Sport, the first ever Sports Council-funded sports development programme, was to help address these issues but not without significant opposition from local centre management and some local governing bodies of sport.

It seems that from these early days I have been fighting what has felt to be a losing battle to address this exclusion and equalise opportunity. Personally, I am quite happy to acknowledge that I and my generation of managers and leaders have failed on the equality agenda and I would argue that the criticism the sector is now receiving about its behaviour and inability to address equality is fully justified. Exposing our failings at this time is not only morally right but it is the first step to facing up to our weaknesses and improving what we must do in the future. Now, after years working to improve how we manage and deliver services to communities, I have been trying to analyse and understand why we have failed.

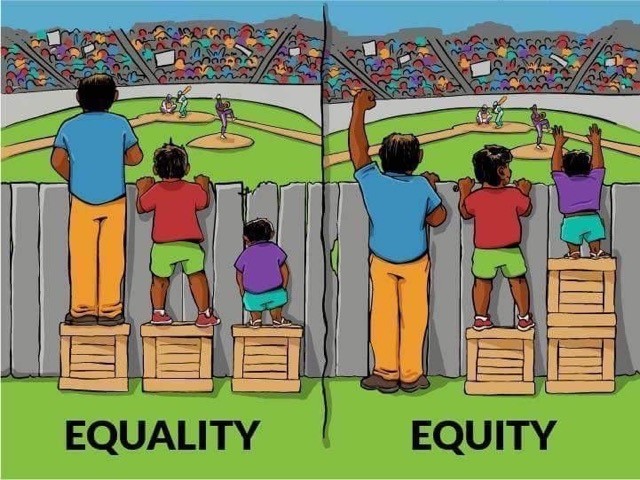

Equality or equity

Perhaps at this point it is worth sharing this cartoon to expose the difference between equality and equity. Often people think if we give everyone the same, that's equality. But as the cartoon demonstrates wonderfully, in order to achieve equality you have to apply equity, what some would call positive discrimination. In the rest of my narrative I am talking about the need to achieve equality through equity, although in many ways simply achieving equality of opportunity would be a good starting point.

Drivers of change

Over the 40 years of my career I have seen governments of every political persuasion commit to equality in sport in policy terms. Each in turn has challenged Sport England, partner organisations and councils to address equality so it is difficult to argue that the reason for failure is a lack of clear policy and political direction.

Despite current austerity, we have also seen periods of significant growth in public funding and National Lottery funding to sport and leisure, both directly through Sport England, UK Sport and the Youth Sport Trust, and, more importantly, local funding through councils, who remain the biggest providers of facilities and services. If you were to add up all the funding available over the last 40 years it would be very hard to conclude that the problem is one of a lack of resources.

We have seen numerous approaches to public service improvement, ranging from Compulsory Competitive Tendering to national and local performance frameworks, including National Performance Indicators, inspection and Local Area Agreements, all seeking to measure our performance and hold us to account for the delivery of increased participation, including improvements in equality. It is therefore impossible to conclude that it is down to a lack of external challenge and scrutiny.

We have seen come and go a very successful home Olympics, won on the basis of our pledge to deliver a participation legacy which many now believe has totally failed despite the huge initial and ongoing costs of delivering more medals. We could not have had a bigger and better international incentive to use elite sport to drive and equalise participation.

We have an unbelievable number of professional bodies representing every conceivable aspect of the sector. Sport England, UKSport, Youth Sport Trust, cCLOA, CIMSPA, SPORTA, UKactive, SRA, CSP network and many, many others who have sought to lead and promote our professional competence to deliver on this key agenda of equality. For a sector so small we probably have a surplus of organisational capacity and capability so we cannot blame this for our failure. In fact when you look at how resilient this sector is in the face of financial adversity, how technically creative it has been in facility development and how innovative it is in supporting athletes at every level, you can't believe the same abilities have not been used to address equality.

The empathy gap

So why have we failed despite all these positive drivers for change? After much deliberation I am left with the conclusion that we simply lack sufficient empathy for those that need to be included and this lack of empathy most critically lies within our senior management and leadership, which means the problem lies in the very culture of our sector. In other words, are we the problem?

What I want to test through debate is the hypothesis that within the sector there has always existed, and still exists today, an "empathy gap" between those that supervise, manage, govern and therefore lead the sector, and the people who have been consistently excluded from the services we provide.

The definition of empathy is "the ability to understand and share the feelings of another." If as leaders we do not understand or share the feelings of those excluded how will we ever see that it is important to change what we do and how we do it so that it is more appropriate for them and their needs. My school sport teacher had no empathy with me as a fat kid who loved sport until I became a competitive player of badminton. The managers in Coventry did not have empathy with the unemployed and young offenders coming into their facilities for 10p because they didn't fit their normal customer profile.

So just for one moment I want you put yourself in the shoes of others. How would you feel as a black person if you felt you were always overlooked or treated differently because of your colour, culture, religion or background? How would you feel as a disabled person if your access was always made just too difficult? How as a gay individual would you feel if you were regularly made to feel uncomfortable or even verbally abused by other users? How would you feel as a woman if you were ridiculed because you didn't look right, have the right gear or didn't know the rules? How would you feel if as a parent you knew you could not afford to take your children swimming this week because you simply had no money to spare or could not commit to a direct debit membership to get a cheaper rate or if the swimming lessons were completely off limits because they would have to be paid for in advance for ten weeks? Can you empathise with these individuals or have you never even thought about it?

If as a receptionist, coach, sports leader, pool attendant or supervisor you lack empathy with these individuals and groups are you likely to ever be able to understand their needs or understand how to create an environment in which they feel really welcome? If you are passionate about sport and have always loved to compete to win, will you ever have real empathy with those who are less passionate about competing and winning and just want to have a go? If as a facility manager you aspire to be commercially successful and be judged only on your financial performance rather than on your social effectiveness will you ever be really committed to creating better access for those that are hard to reach?

As a club or facility manager do you make your pricing, programming and marketing decisions based on empathy with the excluded or based on your own personal values, experiences and aspirations? Does your own experience of the world dictate the environment you create? Are you more likely to design and sustain an organisation that reflects your view of the world and are you more likely to recruit people that share your views than have different ones? If you behave in this way as a leader you will be creating an "organisational culture" and a set of behavioural norms that are not premised on empathy with those excluded but empathy with those that are much more likely to be the “usual suspects”: the included and those just like you.

What if on the other hand you are not the manager but you are part of the governance arrangements that hold to account the management? What if you are a councillor or on the board of a private company, the trust, the CSP, the NGB or local club? What if you and all the people who you govern with also hold the same values and all share the same view of the world as the management? Do you simply reinforce the culture or do you demonstrate empathy with those excluded and in doing so challenge the performance of the organisation on issues of equality?

How did we get here?

So if there is a lack of empathy in the sector what has caused it?

Ignoring for now the elite end of the sector where there appears to be a very significant empathy gap, let us just focus on community sport. For ease of debate let us assume that the community sector can be divided into three primary groupings: NGBs and associated sport clubs; local facility operators, whether council, trust or private; and what I will call community providers. I have deliberately avoided using the term ‘sports development’ because it is a function that exists across all three groupings and can mean very different things in each context. By ‘community providers’ I mean organisations specifically set up to address participation in disadvantaged communities.

There are some cultural aspects that are common to all three groupings and other aspects that are interestingly different.

Representative workforce and leadership

The main thing that is common in traditional providers and operators is the make up of the workforce, which remains predominantly white male with fewer women, black and ethnic minority and other minority staff. In my 40 years working in the sector this has only marginally changed. Even today just look round at any sector conference and you will see what I mean. Most present, particularly managers, all still predominantly white and male. And when you look round the governance tables of these organisations what do you see? A similar picture. When you look at the sector leadership, as in the Women in Sport-Beyond 30 report shows, there are few women in senior positions and still fewer from black and ethnic minority backgrounds.

http://www.womeninsport.org/resources/beyond-30-report/

If change is happening it is slow and if empathy is the key problem the white male bias at an operational management level will make it very difficult even for the best of our leaders.

Historically, most people working in NGBs and clubs, and many working in facilities, have entered the industry because of their passion for or interest in sport. Increasingly, they come in with a sport medicine, coaching or sport management degree. Many also still enter as a result of playing and volunteering in their local sport clubs. The same is equally true of many of the governance structures.

Having passion for something is not in anyway a negative. It drives most professions particularly across cultural services, medicine, science, etc. We rely on the passion to motivate us and give us the aspiration to develop and move on and upwards in our careers. But an unquestioning passion can also act as a barrier to developing empathy with those that do not share the same passion. Many people, particularly girls and women, still say they are put off sport by sporty people. The success of the This Girl Can marketing adverts is premised on presenting a very non-traditional set of images of women to women and it does appear to be working. Promoting difference can be as important as promoting the passion.

Equally worrying therefore is that when I talk to final-year sport students at some of our universities I still see the same imbalance in terms of students being mainly white men who are on the course primarily because they are passionate about sport. This suggests that we will continue to feed the sector from a similar pool of potential employees for some time to come. For many universities these sport courses are cash cows earning vast fees for limited learning costs and are churning out far more students than the sector needs, sometimes under-skilled for the challenges we now face.

But when we look at community providers we do see some notable differences. The workforce is often much more representative of their target audience and very often the staff and, more importantly, the leader is not "of the sector" but has come into the role from another social-based profession. These leaders tend to create a very different organisational culture and staff appear to show much more empathy with the participants. Community sport outreach programmes are often far more reflective of community development work and youth work than traditional sport coaching programmes, which may explain some of their success.

The issue of a representative workforce was identified in the latest government and Sport England strategies with the intention to address this in new workforce plans. Given Sport England are currently working on workforce and they have given funding to CIMSPA to develop workforce standards, it will be interesting to see what action will follow to address under-representation in the workforce at all levels. Training and, more importantly, leadership development has been seriously limited by austerity but even allowing for resource scarcity, how much equality training goes on as part of customer service training and how far is equality embedded in new the standards for developing managers? Are we prepared to follow the example of Starbucks and deliver mass racial bias training? However, I believe it is at the leadership level where change must happen urgently. Unless we fundamentally change the make up and focus of senior management teams and governance structures we will not see the cultural change we need. Perhaps we need to start with the leaders?

Organisational performance

Although I cannot share specific data relating to NGBs and clubs, there is a common perception that they have not generally performed well in terms of addressing equality, although some have performed better than others. The recent debate about funding basketball has been interesting in that much of the argument has been that representative participation should be judged more highly in terms of elite funding. The sport has argued convincingly that it is more representative in terms of race and social/economic status when judged against other sports with perceived better medal potential. The Olympic legacy was squarely placed in the hands of NGBs, with funding switched to support them raise participation levels and equality. The general consensus is that many have disappointed, hence the latest funding strategy that incorporates a broader range of providers. Is it fair to assume that, despite whole sport plans establishing targets to address participation and equality with performance based funding dependent on achievement, there was still too little progress? If so, there remains some interesting challenges in clubs and NGBs at both operational and governance levels to change their culture if they are to seriously contribute more to health and wellbeing through activity, particularly in those communities with the most health needs. For many clubs and NGBs moving from making the active more active to making the inactive active will be a major challenge but it is not impossible with the right leadership.

For facilities the challenge is no less daunting. My early Action Sport experience in Coventry and across the West Midlands showed that accessing the traditional facility market for many is difficult. Price was and still is the biggest barrier but having the right clothing and equipment, and transport and distance, are also barriers, as is the social welcome. Put simply, if you make an effort to attend and don't see and meet people who look, sound and behave like you, you don't return. These lessons could have been learnt 40 years ago but even now I see marketing material that puts people off, hear stories of poor first attendance experience and see pricing policies, membership schemes, booking arrangements and programming that are totally alien to those already excluded.

When Compulsory Competitive Tendering (CCT) was introduced in 1980s I found two very different reactions among managers. Some who were worried about creeping commercialisation were quick to form trusts in order to protect the social value of the service and maybe their own jobs, while others aspiring to compete with their private sector colleagues could not wait to operate in this new commercial world. For some the inbuilt desire to compete and win in sport was simply transferred to the balance sheet. Some even started their own companies.

When Best Value replaced CCT I was instrumental in the design of the National Performance Indicators, which sought to measure increases in participation as a good proxy measure of health improvement. They were not generally welcomed with open arms. Many facility managers did not like being held to account against measures that included improvements in equality. They were much more comfortable being measured on usage levels. They became even more alarmed when the national data showed that performance overall was not improving significantly and performance was variable across locations and types of provider. “The data was wrong”, “The measurement methodology was flawed”, “Our own data tells a very different story”, were common retorts I heard rather than an open, honest debate about why performance was simply not good enough.

Although the Best Value regime was instrumental in successfully positioning sport and physical activity against health outcomes, many in the sector welcomed the demise of Best Value. As in the NGBs, performance accountability was not widely welcome or enjoyed. It feels as if as soon as our failure to address equality is exposed we hide from the evidence. I simply ask, why?

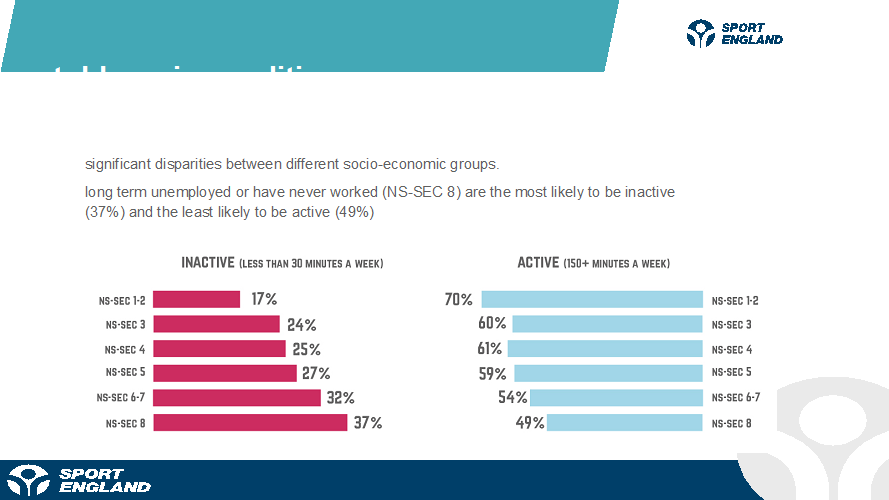

So just as Best Value was quickly being replaced with austerity the health professionals were finally acknowledging what a valuable contribution sport and physical activity makes to health and wellbeing. But over the last decade just as the evidence of impact has mounted, the resources to do something about it have been slashed. The health sector is finding it hard to switch to the prevention agenda but has grasped the value of physical activity. Funding sport and physical activity through health commissioning was for a while seen as a potential way of replacing other forms of subsidy but, as my work with cCLOA for Sport England showed, sport and physical activity providers did not generally understand commissioning, did not have good relationships with health and social care commissioners, and were viewed by commissioners as being only interested in the already active, income for their facilities and focused on sport rather than activity. The health sector knows that although improving everyone's health is a desire, its priority is to address health inequality and the real challenge is improving the health of those most in need where the cost savings and long-term benefits are greatest. Although everyone needs to be more active, those in lower socio-economic groups have the most to gain so it is among these groups where a focus is required, hence the call to "get the inactive active not the active more active". Looking back on this work, it is possible to conclude that there was simply a lack of empathy between the two professions, a gap that needs to be urgently bridged. If the sector is to make a difference to health outcomes it must be prepared to focus on these priority communities and not its traditional market; and there lies the challenge when additional earned income is so desperately needed just to survive.

The facilities sub-sector has increasingly found itself coping with austerity together with demands for cost reduction and greater income generation, placing constant pressure on hard-working staff to deliver more with less. Councils, the biggest providers of local facilities, have seen unprecedented cuts in their funding, which in turn has forced many to reduce or remove entirely the subsidy they provided to sport and leisure. Although some have reinvested in new facilities to increase efficiency and to focus new provision on meeting local priority health and wellbeing outcomes, some councils have simply closed their facilities or transferred them to other providers with no accountability for outcomes; some have used their facilities to maximise income and redirect the profits to other budget areas viewed as more important, mainly social care and children’s services. There is mounting evidence that while operators have significantly improved efficiency, it has often been at the expense of effectiveness as traditionally hard-to-reach groups have been edged out by price increases, membership schemes, changes in programming and aggressive marketing to the better-off.

At the same time community programmes and sports development teams have all but disappeared or been hoovered up into facility contracts. Under increasing financial pressure, some facility operators will then only address health and wellbeing objectives if paid an additional fee, frustrating councils even further to a degree where they choose to retender or opt out of the service altogether.

As chair of the Quest and National Benchmarking Service (NBS) board (which incidentally is also mainly white male in make up), I regularly receive reports about the facilities management part of the sector. The data presented clearly shows that among those using Quest as a mark of quality and an improvement tool many are still uncomfortable about being judged on their approach to delivering social objectives. Far fewer choose modules that test community participation and health improvement than the more traditional service and management modules. Take up of the new Active Communities product, which has replaced sports development, has also been slow despite its clear alignment with the new Sport England strategy. Quest could be a very valuable tool to test how good you actually are in terms of addressing equity but only if you are prepared to expose yourself to the test.

The National Benchmarking Service (NBS) annual report over the last two to three years has gradually revealed a similar pattern. Austerity and the desire to see reductions or the removal of subsidies in the management of facilities have driven significant improvements in operational efficiency. The benchmarks clearly show an increasing number of centres operating at breakeven or even in profit, particularly where investment in new facilities has taken place. However, the results have also shown a compensating worsening in the effectiveness or access performance measures. Clearly the composite picture shows how increased use, increased prices or the greater use of direct debit-based membership schemes has benefited efficiency at the expense of inclusion, with a clear suggestion that the hard to reach are getting squeezed out of more commercially operated facilities even where the operator is a trust.

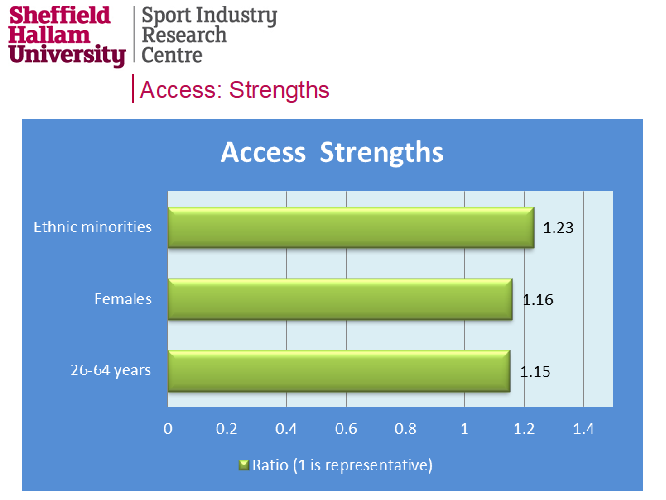

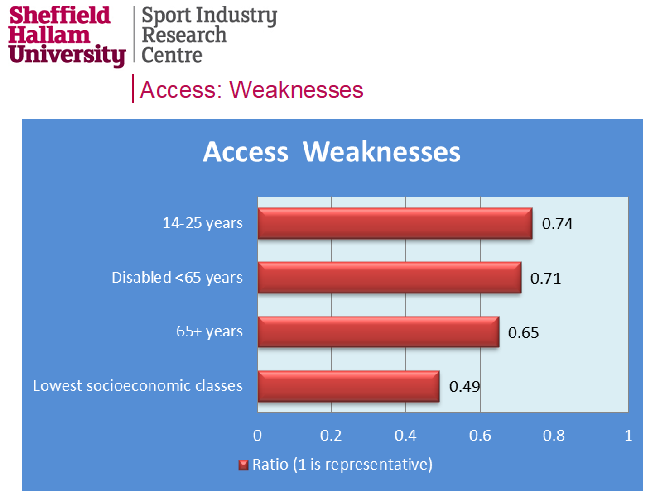

But it's not all bad news. As the following graphs show, the 26-64 year olds, women and ethnic minorities are over-represented but the 14-25 year olds, disabled people, older people and low socio-economic groups are under-represented, the later seriously so, the very groups that need to improve their health and wellbeing the most. What is also interesting is that when offered a choice most operators have chosen to only assess themselves against the efficiency criteria, avoiding altogether the access assessments and showing clearly what matters most to them.

The trust sector was set up to protect facilities from what was seen as creeping commercialisation, to advocate and address social value, and protect the more deprived communities; this is still the claim of SPORTA today. But are they actually capable of doing this without ongoing council subsidy? The data above suggests that even trusts are finding it hard to remain true to their values but is it simply austerity stopping them or have they also lost the empathy for what they claim to value?

In the few community recreation projects that remain we find different results, driven perhaps by a very different culture and leadership that appear to demonstrate real empathy with the deprived and excluded communities.

In Birmingham Karen Creavin has overseen the growth of the wellbeing service that provides a culturally very different offer to the most deprived sections of the community. Through BeActive, Active Parks, Active Streets and Big Birmingham Bikes she can demonstrate much more representative participation, as shown below. BeActive provides some free time at every facility across the city but more free time in areas of deprivation. Although a key policy tool to deliver health benefits to all, negotiating suitable space in those facilities now externalised from the council remains a challenge for her. Despite strong political leadership in Birmingham, in order to survive the financial cutbacks they have decided to externalise the wellbeing service into a social enterprise business model with an ongoing council subsidy only for a time-limited period.

Other socially focused projects, like Street Games under the leadership of Jane Ashworth, also demonstrate far greater empathy with the deprived communities they work with. However, these too rely on external funding to survive.

Does equity depend on subsidy?

So does this simply tell us that without financial subsidy the sector cannot address equality and only by increasing subsidy can we close the equality gap? Personally I don't think this is the case as there are huge variations in performance on equality in both the NGBs/clubs and the facilities; plus there is loads of good practice in community-based providers. I would strongly argue that where there is good leadership and real empathy for the excluded communities, innovation and creativity have and will find ways to address the problem. Where there is the will ways can be found.

Here is my challenge to the sector. Inequality in participation cannot be defended any longer, either morally or on business grounds. None of us should be willing to defend our current failures any longer and if we are to continue to position ourselves as central to addressing health improvement we must also be committed to addressing health inequality. This means that as a sector we must do something to improve everyone's health but also that we must do more to improve the health of those in greatest need. If resources are scarce that means we must be prepared to prioritise. We must focus on equity not just equality.

Personal and professional leadership

My hypothesis is that 40 years of failure can only be explained by a lack of empathy within the sector for those who have remained excluded from it. We each have to assess our own values and our behaviours. As leaders we need to focus on delivering the change needed across the sector. If this means changing the make-up of the workforce and making it more representative we must do so. If it means stopping employing those who are only passionate about sport and employing those who are passionate about equity we must do so. If it means using customer care training to help the workforce to better understand and empathise with those excluded we must do so. If it means cross-subsidising the less well-off we must do so, while also remembering that price is not the only barrier. If it means being more prepared to measure ourselves on equality and address any poor performance we must be prepared to do so. If it means our governance structures holding managers to account for poor performance on equity and if necessary changing them for managers who can better deliver equity we must do so. If it means standing up and questioning poor ethical behaviour in our elite sport and saying that these behaviours are wrong and detrimental to increasing and equalising participation we must do so.

So do you have an empathy gap?

Martyn Allison has worked in and with local government and its partners for over 40 years, serving as a director of leisure, an assistant chief executive and a national adviser for culture and sport with the Local Government Association. He is a fellow of CIMSPA and chair of the Quest advisory board.

The Leisure Review, September 2018

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

![]() Download a pdf version of this article for printing

Download a pdf version of this article for printing