Packed tight: driving on the shoulders of cycle pioneers

An inconvenient truth for transport

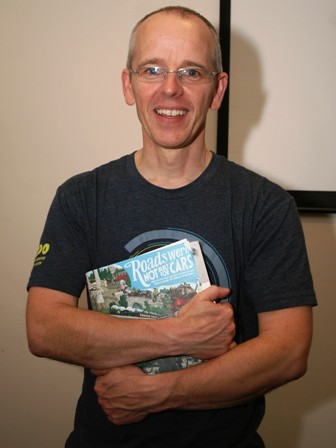

A new book about the history of cycling reveals compelling evidence of the extent to which the modern road system, and indeed modern motoring itself, owe their existence to the pioneers of two-wheeled transport. The Leisure Review heard Carlton Reid explain why Roads Were Not Built for Cars may make uncomfortable reading for car-focused officialdom.

Packed tight: driving on the shoulders of cycle pioneers

Carlton Reid has written a surprising book about cycling. The surprise is not that he wrote a book about cycling – Reid is the editor of Bike Biz magazine, the trade journal of choice for the UK cycle industry, and a sought-after commentator on all things bike-related – but rather that in researching the history of the relationship between roads and bicycles he himself was surprised by what he discovered.

His original idea had been to explore and describe the role of cycling in the creation of the road network but the book that emerged from four years of research and writing was that and rather more. Not only does Roads Were Not Built for Cars tell the story of how roads were saved by cyclists, it also explains how cyclists created the modern motor industry and how much of this history had been systematically suppressed by those with a vested interest in ensuring the dominance of the automobile.

Speaking on the eve of the launch of the first edition of Roads Were Not Built for Cars, Reid explained this inconvenient and uncomfortable truth.

“My first starting point was looking at how cyclists came and saved roads,” he said. “But my research meant that I discovered that cyclists and motorists were the same people. No one seemed to know that cyclists were the pioneers of motoring.”

In the very early days of cycling, Reid explained, few would have imagined the bicycle as a universally a popular mode of transport. “You might say that cyclists now are very similar to those in the 1870s: it was very much a middle-class thing. The bicycle created independent mobility and cyclists were the transport progressives of their day. The same people that embraced the bicycle then went from cycling to motoring as part of the elite.”

Roads Were Not Built for Cars includes the stories of ten motoring pioneers on both sides of the Atlantic, all of whom developed their automobile companies from roots within the manufacture of bicycles. Men such as Lionel Martin, co-founder of Aston Martin, who was a cycling pioneer and was killed while riding a tricycle by, of course, a car. Henry Ford’s first motor vehicle was a quadricyle that used bicycle technology. A keen cyclist, Ford continued to ride his bike to work even in his seventies, by which time he was the most famous car manufacturer in the world. Henry Rolls, eponymous founder of Rolls Royce, had a Cambridge blue for cycling. In his pursuit of transport innovation he bought a aeroplane from the Wright Brothers, who were also bike manufacturers.

William Morris, who founded one of the great British motoring marques and, according to Reid, “was the Bill Gates of his day”, built his first vehicle, a bike, in the shed his parents’ garden. A keen and successful racing cyclist, he kept his cycling trophies in his office long after he became Lord Nuffield. In Germany Karl Benz, used his experience as a cyclist to build his first car from bike parts. In Italy Bianchi, then as now a celebrated cycle brand, was creating “the car for the connoisseur”. Reid’s research revealed more than 60 car marques with cycling origins but none have been keen to have these cycling roots remembered.

In the 1890s bicycles were at the cutting edge of technology – half of the US patents granted during the decade were for bicycle innovations – and cycling enthusiasts were part of a transport elite. Despite being few in number, cyclists proved to be among the most influential innovators and campaigners of their age. In 1886 cyclists in the UK founded the Roads Improvement Association to call for the remaking of a road network that had been neglected and in some areas simply abandoned following the arrival of the railway. In the USA cyclists followed suit with the Good Roads Movement, which campaigned for asphalt roads to meet the needs of the growing number of people discovering the bicycle as a means of fast and reliable transport.

Although the bicycle only started to become widely adopted by the working classes in the 1920s, cyclists and cycling continued to be associated with innovation. Racing cyclists became racing drivers. The Napier, one of the leading British racing marques, was famous for using aluminium in its cars but the technique had first been applied to make bicycles. Albert Champion, a French racing cyclist and winner of the Paris-Roubaix bike race, founded not one but two of the world’s biggest spark plug companies (the Champion Ignition Company and then the AC Spark Plug Company) in the US. In the UK Alfred Harmsworth learned his trade as a journalist on Cycling magazine before founding the Daily Mail and creating a new style of journalism for its tabloid format.

By the 1930s cycling had left behind its elite origins to become a proletarian pursuit, transforming the lives and aspirations of generations of working-class people. However, even in the midst of this transformation cycling began to be edged out of its position on the roads. The car companies that owed their development to the bicycle began to lobby government for funding for roads, investment that would feed the market for their products. Having saved the road network, cyclists were gradually but determinedly removed from the roads to make way for cars. In 1910 there were 40,000 cars on British roads and 12 million cyclists but for the next century and beyond transport funding went almost exclusively into motoring infrastructure. By the 1950s cycling in Britain had begun to decline and by the 1960s had all but disappeared as a recognised mode of mass transport.

The rebirth and rise of cycling in the UK in the 21st century is a fascinating coda to Reid’s history of the road network and its relationship with the bicycle. Having floated the idea of Roads Were Not Built for Cars as a publication on Kickstarter, Reid was pleasantly surprised by the initial level of interest and more than surprised by the speed with which the first edition of 1,000 issues sold out; it took only a couple of weeks. Now available in digital formats, the second printed edition of Roads Were Not Built for Cars is now in production, as is a new title, Bike Boom, exploring the recent renaissance of the bicycle in popular culture. With cycling now creating a new context for transport debate, the impetus for bicycle use seems to be growing. Now the only surprise for Carlton Reid is that after the best part of three decades as a journalist he gets described as a historian.

You can find all the details of Roads Were Not Built for Cars at www.roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com and details of Bike Boom via www.kickstarter.com

The Leisure Review, May 2015

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

![]() Download a pdf version of this article for printing

Download a pdf version of this article for printing