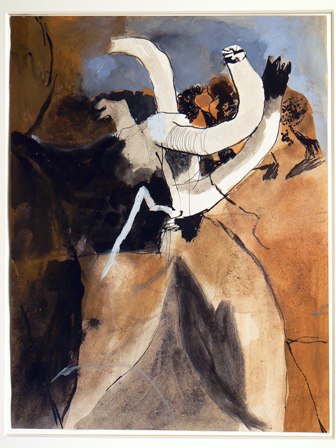

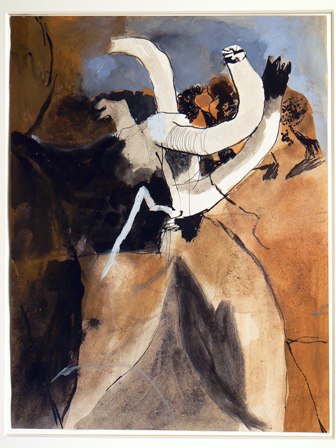

Tree Forms by Graham Sutherland

An unfinished world

Modern Art Oxford is presenting An Unfinished World, an exhibition of the work of Graham Sutherland. Nick Reeves went along to see what this show might reveal about one of Britain’s most under-celebrated artists.

Tree Forms by Graham Sutherland

Off to Modern Art Oxford (MAO) with your editor to view the latest attempt at a revival of Graham Sutherland’s reputation. Born in 1903, by the time of his death in 1980 Sutherland’s reputation was already eclipsed by a younger artist he mentored for many years, Francis Bacon. Sutherland’s influence was greater than the great libertine, Bacon himself, would have cared to admit but it would be a shame if Sutherland’s legacy was simply that of a good painter who inspired a greater one.

In the 1960s and 1970s Sutherland’s reputation was high and his prices reflected his widespread popularity. Collected and admired on the continent (the Italians especially took to his graphics and pursued them avidly), Sutherland lived mostly abroad, despite the many beautiful landscapes he made in Britain and especially in Pembrokeshire. He painted in the English romantic tradition that goes back to Samuel Palmer and John Linnell in the early 19th century.

It was said by some that he had lost his inspiration by moving to the south of France and severed an involvement with the spirit of place forged in the wild and geologically ancient environment of Pembrokeshire in the 1930s. However, Sutherland had already started to go back to Pembrokeshire and to reconnect with the source of his vision. He made his first trip back to Wales in 1967, returning regularly until his death. This new stimulus is evident in has late work, though he never quite recaptured the effortless lyricism of his early Welsh period when he painted nature in terms not so much of symbols as of a visionary transformation of things perceived; and where the vision is more real than the object of nature.

After his death Sutherland’s reputation collapsed. Many felt he had been overrated and oversold. He was out of fashion for twenty years, during which time his work was hardly shown and good examples good be bought quite cheaply. Put simply, Sutherland’s work was lost to a whole generation of art lovers who now have a chance to enjoy it for the first time. And, despite a recent resurgence of interest, he has not recovered his former, but very brief, position as Britain’s greatest modern painter. Bacon on the other hand, an artist of cities and danger, clubs and drinking dens, captured the angst of the age and, reflecting its anxieties with alarming intensity and power, took that particular accolade.

Today British 20th-century art in general is being reassessed and the big beasts such as Moore, Hepworth, Nicholson, Piper and Sutherland are subject to renewed study. Sutherland’s early work is more easily acclaimed to the detriment of his later career, as was evident from the major show of his work at the Dulwich Picture gallery in 2005. But surely more work needs to be done on the whole of his achievement, culminating in a carefully curated museum retrospective in the near future. The current, and hugely enjoyable, show at Oxford follows prevailing opinion by sticking mainly to his early work.

The exhibition is called An Unfinished World (on until 18 March) and is curated by artist George Shaw, a Turner prize nominee who principally paints the Tile Hill housing estate in Coventry, where he grew up. Coventry, of course, is where Sutherland’s huge tapestry of Christ adorns the modern cathedral, a popular piece of modern public art that helped establish Sutherland’s reputation and make him a household name in his lifetime. It also brought him valuable commissions and made him the renowned painter of portraits of Churchill, Beaverbrook and Somerset Maugham. However, I agree with Shaw that the tapestry is “wonderfully irrelevant” and, in terms of artistic merit, is easily trumped by the hundreds of beautiful studies for it and which are now on display in the Herbert Art Gallery opposite the cathedral.

Shaw’s take on Sutherland is informative and new. He says that Sutherland was “not interested in things, certainly not in things as they are, but perhaps in what they once were and will be, of what they could be... His suns, hills, valleys, roads, roots and skies are not of our encounter with the world around us; it is a second-hand deliverance, used up, tattered, passed on – the marks of its previous owners all too apparent. There is nothing new and nothing finished in Sutherlands world.” So the theory behind the exhibition is clear from the title and from Shaw’s own words – that nothing is finished. But that is the nature of the works on show. They are working drawings, sketches and gouaches on paper, mostly squared-up and evidence of the process by which a larger finished painting is arrived at.

Our society prizes drawings in a way that would surprise artists of previous centuries, who saw them as a means to an end and not worthy of preservation. Sutherland, however, was the product of a fragmented modernist culture, an artist trying to make sense of a landscape literally and metaphorically devastated by world war. His work can be seen as fragments but his vision, his world, is no more unfinished than any artist’s.

Ignoring the Oxford show’s intellectual pretensions (Shaw’s fault not Sutherland’s), it is a wonderful selection of 85 mostly small works in the huge, white, barn-like upstairs space of the museum, and three smaller rooms. The best are in the big room: swarms of dabs or cup-shaped brush-marks, scrawls and extended stabs of pencil-line, brushy areas of soft colour, poignant but somehow dingy – green-blue, dim yellow. This is landscape environments (jargon-ised – as everything is these days – as natural capital) explored through the mind, allowing all sorts of levels and degrees of interpretation from the stagy to the neurotic. The sun sets between the hills, yet the space conjured up is at once compelling and sometimes unconvincing, the overlays of watercolour wash blurring forms and outlines into a subfusc vibrancy. Dark traceries of ink huddle round colour accents in crayon or pastel, like flashes of light or tongues of flame. Here is richness, here is energy –in one of the most rewarding exhibitions I’ve seen for quite a while.

So, suitably intoxicated, your editor and I repaired to a pub (delightfully unencumbered by music or tourists wallowing in iPad-heaven) for a few pints of Young’s ‘ordinary’ and a little reflection. Then back to the museum for a Sutherland tour and talk by one of the curators. These talks are informative and well worth the effort but check before you visit; these talks – like Sutherland’s reputation – are not well-publicised.

Nick Reeves is the executive director of CIWEM and an exhibited artist of some repute.

Image courtesy of Modern Art Oxford. Find them online at www.modernartoxford.org.uk

The Leisure Review, March 2012

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing