Johnson versus Lewis: a black hat/white hat kind of thing?

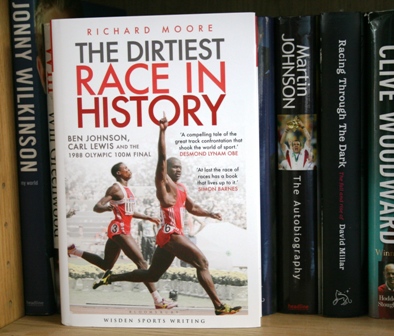

Does a new book about an historic race offer insights into the present state of the Olympic family? We read The Dirtiest Race in History to find out.

The Leisure Review has met journalist and author Richard Moore. And read some of his stuff. He spoke at the 2009 Scottish Sports Development Conference at which we were the event’s communications partner and we found him “scruffy, if ironic”. We then read his first book, In Search of Robert Millar. Having been mightily impressed with his story-telling, journalistic persistence and sensitivity, our considered view is that he may have sartorial tidiness issues but he really can write about high-level sport, which is good enough for us.

Perhaps more importantly it is also good enough for Wisden Sports Writing. This new imprimatur – Moore’s book is their third – is an offshoot of the cricketing almanac which aims to “showcase brilliant writing and to produce books that are not just about sport. They are about life.” Having had the chance to read the first of the books, a series of essays by the non-pareil Patrick Collins called Among the Fans: a Year of Watching the Watchers, we are confident that in partnership with publishers Bloomsbury they have hit on a winning formula.

The Dirtiest Race in History examines the 1988 Seoul Olympics men’s’ 100 metres final which saw the culmination of Ben Johnson’s and Carl Lewis’ sprinting rivalry and, when the former tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs, the start of his life as “the ultimate sporting pariah”. Moore uses extensive research, new (and old) witness interviews and a library of published reflections to tell the story of the “build up to the race, the race itself, and the fallout when the news of Johnson’s positive test broke” and he produces a mirror ball of a book. It shimmers, it glints with promise, it has an attraction beyond the assimilation of the countless, sometimes tawdry, shards of information and opinion which Moore has brought together but its real effect is only revealed when the light of the 2012 Olympics is shone on it. Then it stuns.

British sports fans of a certain age will remember the shock of Des Lynam’s late-night revelation that “Ben Johnson has been caught taking drugs and is expected to be stripped of his Olympic 100m gold medal” or recall the halting words of IOC spokeswoman Michele Verdier that Johnson had tested positive for Stanozolol as the leaked reports were officially confirmed. However, it is not Johnson’s cheating which earns the race the “dirtiest race in history” soubriquet.

In his 300 pages Moore brings his spotlight to bear on the other seven runners in the final, only two of whom were not later tainted by the stain of drug-taking; the sports politicians who were complicit in hiding positive drugs tests; members of Carl Lewis’ entourage who, conspiracy theorists (and Johnson) say, spiked Johnson’s post-race drinks; commercial sponsors who wanted to see “clean” competition and pressured sporting bodies to ensure they appeared that way; marketing companies; sporting goods companies; doctors; chemists; coaches; and a racist media.

The corruption of moral principle which is required to stage an Olympic Games is exposed in hints, assertions and cold, hard facts. Although Moore draws no inferences for the 2012 Games, it is not hard to extrapolate, through the prism of his investigation, that only the naïve would imagine London 2012 to be free of corruption.

In a week when drugs cheat Dwayne Chambers and Christine Ohurugo are waved through into the Great Britain athletics team by the national broadcaster without mention of their cheating pasts, when sponsors UPS are found to be using their monopoly to charge £25 per delivery to the Olympic site for goods sent with other carriers; when world number one Aaron Cooke is faced with taking the governing body of taekwando to the high court to reverse an “unlikely” selection decision; when athletes are forced to sign away their rights to wear anything other than Adidas on their days off to appease a sponsor; and when countless “plastic Brits” are being confirmed as members of “our” wrestling, volleyball and handball teams, it is hard to maintain any sense that 2012 will be anything other than an extended exercise in compromised and compromising commercialism.

It is to Moore’s credit that the minutiae of his investigations make for easy reading. Occasionally the relationships between protagonists can become unclear or the import of the facts on offer can become distorted but at least Moore does not confuse the reader with moralisation. He seems to present the case and allow the reader to judge, although as any student of Derrida will acknowledge “every decoding is another decoding”.

Take, if you will, the issue of which of the two protagonists was “the good guy”. Clearly, with Johnson the guilty party, he must be wearing the black hat of the villain? Carl Lewis certainly sought to portray himself as the good guy, affecting all-white tracksuits, shaking every competitors hand before each race, and being available and affable to the media. But Lewis had failed a drugs test at the 1988 US Olympic trials, his athletics career was merely a precursor to a proposed assault on Hollywood and/or a singing career, and he had a written marketing plan for his own brand which he worked assiduously to deliver.

In this respect Moore does make a judgement, coming down clearly on the side of Johnson over Lewis. Having met them both recently, he sees Johnson as sinned against and sinning, a man with some perspective on his crime and some degree of loyalty to his past and the people in it. Lewis, whom Moore struggled to interview, he portrays as cold, isolated and without real purpose. He quotes a conversation in which Lewis, who once aspired to emulate Michael Jackson, implies that the only way Usain Bolt can be as good as he is (which is to say better than Lewis) is because he is doping.

Perhaps while Johnson was injecting the steroids Lewis was, to use an increasingly apposite Olympian phrase, drinking the KoolAid; an altogether more pernicious concoction.

The Leisure Review, July/August 2012

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing